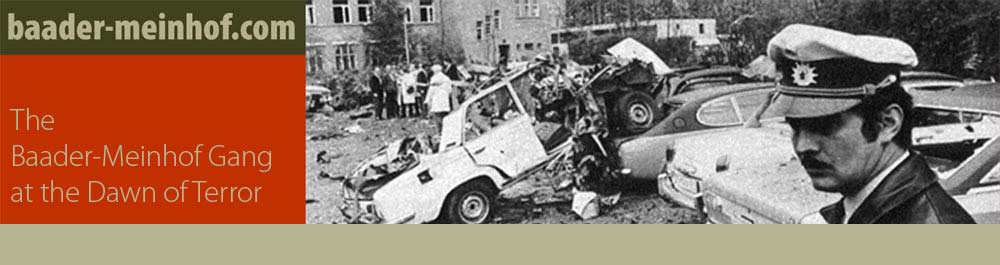

"October 18, 1977"

An exhibition by Gerhard Richter

Permanent Collection

Museum of Modern Art

by Richard Huffman, baader-meinhof.com

April 2002

"Gerhard Richter is a bullshit artist masquerading as a painter," writes Jed Perl in the lead sentence to a cover story about Richter in the April 1, 2002 issue of the New Republic. Perl's commentary goes downhill from there.

Daniel Kunitz, writing in slate.com, is a little more balanced. Kunitz takes Richter down a notch or two, but generally reaffirms Richter's importance and talent.

|

Hanged |

Both articles arrive on the eve of a major retrospective of Richter's work at the Museum of Modern Art. The centerpiece of the exhibit is Richter's 15-painting cycle, "October 18, 1977," which explores the imagery associated with the Baader-Meinhof era. MOMA added the cycle to its permanent collection recently, and the retrospective serves as its coming-out party.

Richter's work almost defies analysis. Is it art? Jed Perl doesn't seem to think so. He indicates that Richter's technique of tracing photographs as source material for his work implies a mind devoid of artistic creativity. Kunitz recognizes the coldness, but sees a method to Richter's madness. He also recognizes a power from viewing Richter's work in person.

Robert Storr, the curator of the MOMA collection and the person who both secured the purchase of the "October 18, 1977" cycle and organized the Richter retrospective, certainly believes that Richter is among the most important contemporary artists. Storr understands that Richter's work can be interpreted as sham or art; his 152-page book about the "October 18, 1977" cycle is essentially a book-length justification for spending such a large sum of the Museum of Modern Art's money on a man who hasn't quite yet been consensually accepted into the pantheon of great modern artists.

Storr's book is flawed in that he offers supposedly dispassionate analysis of the controversy over MOMA's acquisition of the Richter cycle without acknowledging his central role in the decision to acquire the works. "In June 1995," writes Richter, "to the surprise of close observers of the scene as well as the public at large, it was announced that October 18, 1977 had been acquired by the Museum of Modern Art for an undisclosed sum." This Clintonian "mistakes-were-made" dissociation continues unnecessarily throughout the book when Storr describes the facts surrounding his purchase.

But this is a minor quibble. When analyzing the actual artwork, Storr succeeds in his argument. Through an in depth exploration of Richter's technique, his critical reputation, and his choice of subject matter, Storr clearly demonstrates Richter's importance as an artist and the importance of his art. Perl just as clearly disagrees; his New Republic piece feels so angry at Storr that I can't help but wonder if Storr and Perl had a childhood falling out and Perl is nursing a lifelong grudge.

The vast majority of Richter's work is immediately accessible. Even the most uncomplicated minds can grasp the cold emotional impact of his fuzzed renderings of contemporary photos. Further context behind the subjects of his paintings is not generally necessary.

But "October 18, 1977" is altogether different. This is a work that is all about context. It is a collection derived from imagery that would have been instantly recognizable to a German who viewed it in the late 1980s. Had he chosen American imagery of a similar time period, one can imagine a painting of Patty Hearst, in full Tania garb, with a beret and a rifle, leaving the bank she had just robbed. One can imagine a grief-stricken girl, her arms outstretched as she hovers over the body of her dead friend on the campus of Kent State University. Richter's images of a glamorous Ulrike Meinhof, the prone body of a dead Andreas Baader, the giant funeral of Gudrun Ensslin, Jan-Carl Raspe, and Baader--these had all been similarly burned into the cerebral cortex of the German who viewed Richter's work for the first time in the late 1980s.

And the story that they told was entirely contemporary. Though "October 18, 1977" featured imagery that was a decade old by the time of his first exhibition of the work, in the late 1980s the Red Army Faction was at its deadliest; ten years after the events of Death Night West Germany was still struggling with the legacy of the Baader-Meinhof Gang. It was impossible to view the works with a dispassionate eye, any more than it would be possible to objectively view a retrospective of modernist portraits of Osama bin Laden in New York City in 2001.

But this, of course, is the great challenge of the work. Whereas West Germans of the late 1980s could not look at the works dispassionately, a contemporary New York audience has precisely the opposite problem. "October 18, 1977" clearly has a shelf life, at least as 1980s analyses of the work go, and the further that the work travels from its geographic and chronologic home, the more the context disappears.

Visitors to the work at MOMA can read detailed placards explaining the paintings. They are also encouraged to buy Robert Storr's book for a more accurate and nuanced understanding. It's not hard to see why: if a visitor wasn't told the subject of the exhibit, he or she would be hard pressed to know what it was about. Even where Richter's source photos were fairly clear cut, such as Baader dead with his face tilted back in a grimace, the resulting painting becomes blurry and indistinct; even if the viewer could recognize that the subject was a dead body, the painting offers no indication of who he was or the context of his death.

Others paintings seem even more obscure to contemporary American viewers. The filled-to-bursting bookshelf? The record player? Where are they from? Why did Richter choose them? The 1980s German would have recognized the bookshelf as Baader's, and understood from press reports that it was filled with dozens of volumes of Marcuse, Horlemann, Marx, Engels, Guevara, and Debray, countering the common perception of Baader as a violent poseur. The record player: symbolic of the freedom enjoyed and exploited by these pop culture heroes. But for a modern American audience, they are simply a bookshelf and a record player, evoking nothing.

|

Man Shot Down |

One doesn't need a placard explaining the background of the Mona Lisa to appreciate it. One doesn't need to have Monet, or Picasso, or Rembrandt explained. So, the argument goes, having to fully contextualize a work that was designed to be presented without context means that the work utterly fails.

I'm not so convinced. Experiencing art benefits from contextualization. Even works by acknowledged masters like Monet, Picasso, and Rembrandt. On a surface level one can enjoy their works for the pure emotions they stir unencumbered by context. But our learning and appreciation is deepened by understanding the context in which the work arose.

That said, devoid of context, Richter's cycle is cold, dreamy, and fundamentally, brilliantly, sad. His technique--or crutch, as Kunitz calls it--of blurring the details of the two-dimensional worlds of found photographs, renders life somehow inert. It certainly puts a distance between the viewer and the viewed; great tension is generated as we are pushed away from subjects that would normally draw us in. Unlike old masters, the only way to discern more detail from Richter's work is for us to move further away.

That was clearly Richter's plan.