The Limits of Violence

Originally appeared in Satya magazine in March 2004

read original article from Satya web site

By Richard Huffman

When I marched in the November 30, 1999 anti-WTO rally here in my hometown of Seattle, the brutal tactics and sporadic yet stunning violence by the Seattle Police felt eerily similar to a catastrophic Berlin protest a generation ago. On June 2, 1967 tens of thousands of young Germans, many of them students at Berlin’s Free University, lined up on Kaiser Wilhelm Strasse early in the evening to protest a visit by the Shah of Iran. By the end of the night, a young pacifist lay dead in an alley, shot by an accidental discharge from a cop who had trained his gun at the student’s head. Benno Ohnesorg’s death would be the unfortunate catalyst for a distressing movement that offers powerful relevance for young Americans today who are considering violent means to effect social change.

After the rally, thousands of angry, frustrated students converged at the Berlin offices of the Socialist German Student Union, which was the leading student organization at the time. Gudrun Ensslin, a young woman with an intense demeanor, screamed to the crowd, “This fascist state means to kill us all! We must organize resistance. Violence is the only way to answer violence. This is the Auschwitz Generation, and there’s no arguing with them!” The leader of the Student Union, firebrand organizer “Red” Rudi Dutschke, was sympathetic to Ensslin’s goals but proposed decidedly different tactics to achieve them. Instead of violence, he advocated for “a long march through the institutions” of power, to create radical change from within government and society by becoming an integral part of the machinery.

Students of modern German history know how these twin philosophies played out over the coming decades. Ensslin helped to form the Red Army Faction, popularly know as the “Baader-Meinhof Gang” (see preceding article). During the next decade Ensslin, intent on bringing a form of Socialist Revolution to Germany, and the 50 or so young Germans who joined her and her boyfriend Andreas Baader, left a trail of destruction through Germany unmatched since the Soviet Army paid a visit in 1945. They blew up buildings and killed American soldiers. They killed the leading justice on the West German Supreme Court. They kidnapped and later murdered Germany’s most noted industrialist, a man who roughly occupied the place Bill Gates holds in the U.S. today. They helped highjack a Lufthansa jet. They blew up the German embassy in Stockholm.

A whole other generation of young Germans chose to take up Rudi Dutschke’s call to action instead. They would be instrumental in the rise of Greenpeace and environmental consciousness in Germany, and would go on to found the progressive Green Party in 1979. Twenty years later the Green Party would be sharing control of the German government.

It’s clear that the Baader-Meinhof Gang and their adherence to violence made a considerable impact on German society; but for a socially-concerned citizenry this impact was wholly negative. Prior to the Baader-Meinhof era, West Germany didn’t even have a true national police force. In response to their terror campaign, the BKA, which later became the German equivalent of the FBI, was built up to massive proportions, with the full power to investigate citizens in ways that John Ashcroft can only dream about. The German government passed sweeping laws that restricted the rights of average citizens, and instituted loyalty oaths for all civil service jobs. Random general searches of citizens’ homes on a block by block basis became common.

In many ways this was exactly what Gudrun Ensslin, Andreas Baader, and their fellow Revolutionaries hoped would happen. They expected that the German state would respond with disproportionate violence and repression; they believed the proletariat population would be shocked from their complacency and would spontaneously rise up, following their lead into glorious Revolution. It didn’t quite work out that way. Rather the German population, angered and frightened by the violence, applauded their government’s repressive response. Seeing the ease in recent years in which President Bush and John Ashcroft were able to pass the Patriot Act and implement repressive programs such as CAPPS II in the wake of the violent shock of the events of September 11 leads me to the unavoidable conclusion that cause-based violence only begets widespread government repression. And this repression invariably is supported by the very population being repressed.

But if that violent subset of the German generation, which found its voice after that tragic 1967 Berlin protest, offers an effective primer on the limits of violence as an effective means of social change, other members of this same generation have shown how a steady, committed “long march through the institutions” can bear fruit.

Last February, when thousands of people were marching in streets across the U.S. against President Bush’s headlong rush towards war, similar protests were held across the globe. Perhaps the most remarkable march was held in Berlin. Nearly one million Germans took to the streets, not to condemn their government, but to praise it for choosing to not participate in an unjust war.

So how did it come to be that one of America’s most powerful allies and one of the world’s leading democracies chose to suffer the wrath of America by staying out of the war? Because a generation of people chose to heed Rudi Dutschke’s call three decades ago. They became civil servants. They got elected to local offices. They became involved in socially progressive causes. They founded and guided the Green Party into becoming a true force in German politics, eventually putting the party in the position to share power with the SPD (Germany’s equivalent of the Democrats) in a coalition government. They took positions of power in the upper echelons of German government, like Joshka Fischer, who became Germany’s Foreign Minister (the equivalent of Colin Powell). And when the opportunity came for a bold choice to stand up to oppressive American pressure to support the coming war, Germany’s government was well represented with members of Rudi Dutschke’s generation, ready to fulfill his legacy, and take a strong stand on behalf of social justice and against unjust aggression.

"The Baader-Meinhof Gang"

Adaptation of material on baader-meinhof.com

Originally appeared in Satya magazine in March 2004

read original article from Satya web site

By Richard Huffman

It wasn’t just about killing Americans and killing “pigs” (police), at least not at first. It was about attacking the illegitimate state that these pawns served. It was about scraping the bucolic soil and exposing the fascist, Nazi-tainted bedrock that the modern West German state was propped upon. It was about war on the forces of reaction. It was about Revolution.

The years between 1968 and 1977 represented the most tumultuous era in West Germany’s internal social-political history. The student protests of 1968 that had promised so much hope, quickly fizzled into riots. Many of the leftist students would follow student leader Rudi Dutschke’s clarion call to gradually change the institutions from within. But a select few of the radicals had no time for any nebulous march—they wanted Revolution now, and sought to kickstart the cause through terrorism. In 1968 Andreas Baader and his girlfriend Gudrun Ensslin attempted to do just that by firebombing two Frankfurt department stores—symbols of capitalism.

The Baader-Meinhof Gang didn’t expect to achieve Revolution by themselves. They assumed their wave of terror would force the state to respond with brutal, reflexive anger; that the proletarian West Germans would react in horror as the true nature of their own government was revealed; and that factory workers, bakers, and miners would rise up and overthrow their oppressors. They assumed they would be the vanguard of a joyous Marxist Revolution.

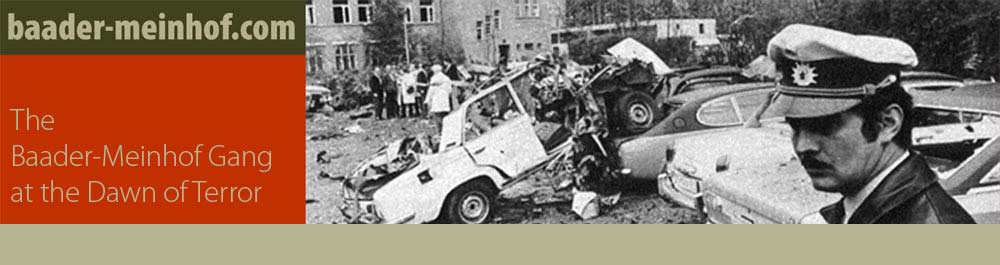

Much of what they assumed about the German state proved true. Light armored tanks and machine gun-wielding police became common sights on the streets of Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich. Police would search entire apartment complexes on the slightest hint of Baader-Meinhof activity. Random police searches of the vehicles of young, long-haired Germans became common. It seemed perfectly clear to the members of the Baader-Meinhof Gang that they had brought to the surface the fascism that had plagued Germany since 1933—a power structure that had changed little since the Nazi regime.

For a time, it seemed as if their leftist urban guerrilla warfare might have a measure of success. Polls showed an extraordinary number of Germans supported their cause in one way or another: 20 percent of Germans under the age of 30 expressed “a certain sympathy” for the Baader-Meinhof Gang; one in ten young northern Germans indicated they would willingly shelter a member for the night. For the leaders of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, this was empowering proof that millions of Germans were lining up behind their cause.

But save for killing a few policemen in shootouts, the Baader-Meinhof hadn’t really begun their Revolution. There were no decapitated GIs yet, no maimed press operators. It was therefore easy to support them; they hadn’t yet truly turned their theory into praxis. This would all change one year later.

After their weeklong campaign of terror in mid-May of 1972, few Germans were interested in marching behind the Baader-Meinhof Gang. After the Heidelberg bomb that shredded U.S. Army Captain Clyde Bonner and his friend Ronald Woodward into confetti; after that same bomb knocked over a Coca-Cola machine, crushing another soldier; after the Frankfurt bomb that sent shards of glass into Lt. Colonel Paul Bloomquist’s neck, severing his jugular; after the bombs placed in the hated Springer press offices in Hamburg injured and maimed 17 typesetters and other workers; after the bomb that almost killed five policemen in Augsburg; after a car bomb destroyed 60 cars in a Munich parking lot of the federal police force; after the bomb planted under the seat of Judge Wolfgang Buddenburg’s Volkswagen exploded, severely injuring his wife; after all of this terror, the Baader-Meinhof Gang had no support. The millions of ordinary Germans, whom the faction’s leadership believed would rise up, never materialized.

Within five days after the bombing spree, they were all in jail. Within five years they were all dead.

The First Celebrity Terrorists

The Baader-Meinhof Gang were the world’s first celebrity terrorists. Although they called themselves “The Red Army Faction,” they were only known in the public’s mind by the last names of Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof, a popular journalist who had helped free Baader from prison custody. Coverage of the group was so ubiquitous that the story index of Der Speigel (Germany’s equivalent of Time magazine) regularly listed a simple “B-M”—no one needed the letters explained to them.

They were the true embodiment of the term “radical chic.” They had style; they set trends. When Andreas Baader was eventually captured in a nationally televised siege in a Frankfurt neighborhood, he had the presence of mind to keep his Ray-Bans on as he was being dragged into a police van, a bullet in his thigh.

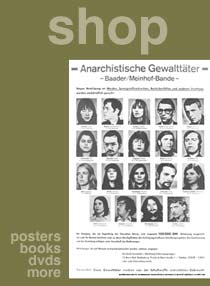

The public and the media weren’t interested in the true dynamics of the membership of the Gang. For most people, the group became a prime vehicle to project their own assumptions, fears, and ambitions. Nothing reflected this more than in the late summer of 1971, when seemingly overnight every bakery window, U-bahn station, kiosk, and lamp pole became covered with wanted posters, supplied by the BKA, the West German federal police force, featuring rows of the faces of almost two dozen young Germans sheepishly confronting them.

The reach of the Baader-Meinhof wanted poster was enormous and unprecedented; seven million posters were printed and distributed across a country with only 60 million residents. The photos on the poster were relatively benign; many clearly came from school photos or from family albums. But if the photos weren’t particularly menacing, the poster itself certainly was; its ever-present nature left many Germans fearing that terrorists were behind every lamppost and phone box. What the authorities did not anticipate however, was that their poster would communicate an equally powerful message—unintended, yet devastating in its allure—to many young German women. Of the 19 faces, almost half were women.

Radicals?

Rudi Dutschke, a brilliant Berlin student leader, advocated a “long march through the institutions.” He proposed a decades-long Revolution by entering the systems of power, working into positions of leadership, and effecting peaceful, gradual change from within. His arguments held considerable sway, inspiring many young Germans to begin their own long marches. Joschke Fisher, Germany’s extraordinarily popular current Foreign Minister, and so instrumental in the German decision to oppose the 2003 American war in Iraq, was the most noted of hundreds of former radicals who deferred their immediate goals and steadily marched into the upper echelons of the German power structure.

But Meinhof, Ensslin, and their cohort were baldly dismissive of this approach. Their very first communiqué made this evident: “You have to make clear that it is…garbage to assert that imperialism…would allow itself to be infiltrated, to be led around by the nose, to be overpowered, to be intimidated, to be abolished without a struggle. Make it clear that the Revolution will not be an Easter Parade, that the pigs will naturally escalate the means as far as they can go.”

Compared with the coming actions of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, the radical German student movement of 1968 was “radical” in name only.

The End

Most of the leaders of the Baader-Meinhof Gang were captured in mid-1972. Their followers would kidnap and kill close to a dozen people over the next five years in an effort to secure their leaders’ release from prison, but it was all in vain. The German government had no intention of releasing them.

The German government used the terrorist crisis to approve new laws giving them broad powers in combating terrorism. Hard-core leftists grumbled, but the majority of the German people were firmly on the side of the government.

After an airplane hijacking by Palestinian comrades failed to secure the release of the three imprisoned leaders of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, and Jan-Carl Raspe all committed suicide deep in the night of October 17, 1977.

Some would say that the era when West German leftist terrorist action seemed like a viable vehicle for bringing about revolution ended then. But the Red Army Faction, founded by Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof, and their comrades, continued right on bombing, maiming, and killing for almost another 20 years. Finally in April of 1998, the few remaining RAF members issued a communiqué officially disbanding the RAF.

For a group whose ideology revolved constantly around self-criticism and reflection, they were oddly incapable of asking themselves the most obvious of questions: have we failed? Could we have ever succeeded? Why hasn’t the proletariat, inspired by their actions, spontaneously risen up and destroyed those that oppressed them?