The Gun Speaks Chapter Outlines

The following chapter summaries are adapted from the book proposal for "The Gun Speaks."

Introduction Chapter

12 pages: The introduction begins with an anecdote describing the event that put the Baader-Meinhof Gang squarely on the German national consciousness: the freeing of Andreas Baader from prison custody with the help of noted journalist Ulrike Meinhof. The three most important characters, Baader, Meinhof, and Gudrun Ensslin, are introduced, each showing telling aspects of their personalities that will be fully developed through the course of the book. Meinhof is nervous, Baader is smug, and Ensslin is confident — together they are about to change Germany society forever.

Though the bulk of The Gun Speaks will focus on the human drama of Ulrike Meinhof and Andreas Baader, the book would be incomplete without some exploration of the zeitgeist of the German decade of 1968-1977. The rest of the introduction will present these fundamental themes:

The members of the Baader-Meinhof Gang were the world’s first celebrity terrorists; indeed they were true media superstars in the relatively new age of television. Because the Baader-Meinhof Gang committed few violent acts during their first two years on the run, young Germans were able to project their own assumptions into a perceived reality of the faction. Young women were especially attracted to the gang; with more than half of its membership being women, the Baader-Meinhof Gang was the most gender-neutral terrorist faction in history. Young men were aroused by the sheer number of women within the gang’s ranks; they assumed that there must be little competition for sexual partners. Leftists worldwide were inspired by this outlaw band that was putting their revolutionary Marxist theory into practice. For the briefest of times, the Baader-Meinhof Gang made terrorism seem not the work of pathological madmen, but the legitimate vanguard of the political discourse of the day.

Part One — The Long March Through the Institutions

Chapter 1 — Ulrike

1934 to 1967, 14 pages: Chapter One steps well back from the May 1970 anecdote in the introduction and briefly tells the story of Ulrike Meinhof. It describes Meinhof’s beginnings: her father and mother dying while she was young, her being raised as a teen by a renowned Socialist philosopher. She marries a publisher of a radical student-oriented magazine and becomes its editor. In 1962 doctors diagnose a large brain tumor in her head that requires immediate removal. Five months pregnant, Meinhof refuses to undergo brain surgery because the doctors cannot guarantee that her unborn twins’ lives will not be endangered. The doctors tell her that she is risking her own life, but Meinhof is adamant. After three months of horrendously painful headaches, Meinhof gives birth to twin daughters. The doctors immediately operate on her head, only to find that the tumor is actually an engorged blood vessel — the doctors put a clamp on it and sew her back up. Over the next few years Meinhof moves into chic leftist society, and becomes a very prominent female journalist. The chapter ends as Meinhof begins to attend the student demonstrations that were becoming commonplace throughout Germany.

This chapter establishes much of the psychological makeup of Meinhof — a women who is extremely successful at everything that she does, yet is perpetually plagued by self-doubt. Meinhof’s refusal to risk her unborn daughters’ lives will reverberate in coming chapters as Meinhof struggles with competing instincts to be a proper mother for her children and a desire to throw her whole bourgeois life away and become a revolutionary.

Chapter 2 — Gudrun

1942 - 1967, 19 pages: This chapter opens with a vivid description of a riot that took place in Berlin on June 2, 1967. Students are demonstrating against a visit by the Shah of Iran when Berlin police began beating them. In the confusion, a policeman shoots a young protestor, Benno Ohnesorg, killing him instantly. Ohnesorg quickly becomes a martyr for the growing radical student movement. A reed-thin young woman attends a student rally an hour after Ohnesorg’s shooting; it was Gudrun Ensslin, screaming hysterically, arguing for violent response.

At this point the chapter shifts to tell of the beginnings of Ensslin. Her father was a Protestant pastor, and she was a bright student. She marries at a young age and has a son, Felix. Through the mid-60s she becomes increasingly radicalized, pulling further away from the mainstream and also away from her husband. The chapter ends with a party in her apartment a few months after the June 2, 1967 riot. At the party a handsome young radical is there; Andreas Baader is calling for a campaign of violence against the German state. Gudrun is aroused.

Chapter 3 — Andreas

1943 - 1968, 18 pages: Like the previous two chapters, this chapter will step back in time and tell of the beginnings of Baader. His father having been captured and killed by the Soviets before the end of World War Two, he was left fatherless like many young Germans. Andreas was an exceptionally spoiled child. He was never pressured to succeed in school, so he succeeded at being a juvenile delinquent instead. He bounced in and out of youth homes, constantly being arrested for petty theft. During the mid-sixties he grows attracted to the growing student movement—not because he had any desire to learn but because of the numerous attractive university “chicks.” What he lacked in intellect he made up for in violent rhetoric. When a young college radical would call for action against the state, Baader would pipe in, arguing for massive violent revolt. The student usually came away impressed by the “dangerous” Baader.

Chapter 4 — Praxis

May, 1967 - May 1970, 59 pages: The stories of the three major characters, Baader, Meinhof, and Ensslin, merge into one story in this chapter, and follow a straight narrative arc for the rest of the book. But first this chapter will look into the extremes of the student movement, exemplified by a West German student commune known as Kommune I. This free-wheeling experiment in communal living shocked and aroused many Germans, mostly for the communard’s embrace of nudity and sex.

Late in May of 1967 two members of Kommune I are arrested and charged with inciting arson. Fritz Teufel and Rainer Langhans had written a pamphlet advocating the burning of department stores as a just and proper attack on American-style Coca Cola Capitalism. After their trial in March of the following year Teufel and Langhans are found not guilty, the judge finding that the pamphlet was written “for theoretical considerations only, not to be taken seriously.” Someone forgot to tell this to the now inseparable Baader and Ensslin. They recruit two friends and head to Frankfurt. The four terrorists plant bombs in two department stores; the resulting explosions cause $200,000 in damage. The proto-revolutionaries are quickly caught.

Back in Berlin a young house painter stalks Germany’s most famous student leader “Red” Rudi Dutschke, shooting him five times in front of his apartment. Dutschke will live, but shocked German students immediately cry for vengeance, and attack the hated Springer Press headquarters (they believe that Springer’s relentless campaign against Dutschke surely inspired the attack on him). Meinhof attends the massive protest against Springer that night and a friend persuades her to use her car as part of the blockade of Springer’s printing plant. Wary of damaging her car, she parks it on the very end of the blockade. As tenuous as it is, this is Ulrike’s first timid steps towards putting her Marxist beliefs into action.

This is an ideal point to explore the Marxist ideology prevalent among leftist German students at the time. They would talk themselves silly debating the various flavors of Marxism, many firmly accepting of the notion of Revolution. However, few were willing to actually become revolutionaries. Most were only willing to participate in a demonstration or two, a method of actionthat was purely reactionary. This is why Baader and Ensslin’s actions in Frankfurt were so exciting to radical Germans; here were two people willing to take proactive revolutionary action.

This is also the appropriate time to discuss press magnate Lord Axel Springer. The virulently anticommunist Springer held a virtual monopoly on the press in Germany, controlling 40 percent of the daily newspaper circulation of West Germany and 80 percent of the Sunday circulation. Springer was the main bogeyman among German radicals, who believed that he was the source of all of their troubles. Unlike most other German businessmen during the Cold War, Springer did not flee Berlin. In fact Springer chose to build his headquarters, a 20-story gleaming glass monstrosity, 30 feet from the Berlin Wall as a statement to the superiority of Capitalism. In case the enslaved East Berlin masses did not get the message, Springer installed a Times Square-style reader board facing the wall to flash the news of the Free World. To German radicals, Springer’s skyscraper represented everything that was wrong with Capitalism.

Baader, Ensslin and their two comrades are tried for the arson late in 1968. Meinhof covers the trial for her newspaper. She finds a hero in Ensslin: a woman who so willingly gave up her life-style and her child for the Revolution. Though they are ably defended by the brilliant Marxist lawyer Horst Mahler, the four revolutionaries are convicted and sentenced to three years imprisonment. After a year in jail, they are granted temporary freedom pending an appeal of their case. When the appeal fails, Ensslin and Baader head underground. They travel to Berlin and meet back up with their former lawyer Mahler, who is attempting to put together an urban guerrilla revolutionary band—the true beginning of the Baader-Meinhof Gang.

Before the fledgling faction can cause much damage, Baader is captured by police. Ensslin is beside herself and can only think of freeing her beloved Andreas. She conceives of an audacious plan to free him using a ruse with Meinhof. Ensslin sets to work on Meinhof, trying to convince her to participate. It did not take long for Meinhof to be persuaded by her hero, Ensslin. The chapter ends shortly before the freeing of Baader —the anecdote that began the introduction to the book.

Part Two — The Terror and the Glory

Chapter 5 — Al Fatah

May 1970 - August 1970, 26 pages: This chapter will focus on the world’s newest Urban Guerrilla faction’s escape from Berlin and their trip to a Palestinian guerrilla training camp. For six weeks in the desert, the 15 or so West Germans learn to shoot guns, fall out of moving cars, throw grenades, and thoroughly annoy their Palestinians hosts.

One member of the clan falls out of favor. Ensslin begins to believe that Peter Homann has betrayed the gang somehow, and demands that the Palestinian leader of the camp, Abu Hassan, kill Homann. Hassan declines, and secretly sends Homann back to Germany alone. In Germany Homann seeks the journalist Stefan Aust, an old friend of Meinhof’s, to help rescue Meinhof’s kids from hiding (Homann had overheard Meinhof plan to send her kids to another Palestinian camp to grow up as terrorists). Aust rescues the twins and returns them to their father.

While the urban guerrilla faction is in Jordan, the West German media, particularly the Springer Press, has a field day. Springer Papers dub them “the Baader-Meinhof Gang,” while more moderate papers prefer the more pedestrian “Baader-Meinhof Group.”

Chapter 6 — Back to Berlin

August 1970 - December 1970, 16 pages: This chapter follows the group as they return to Berlin. Horst Mahler conceives of an audacious plan to rob four banks at one time. During the bank raid that Meinhof was in charge of, she only gets about DM 5,000; she misses a bag containing DM 100,000. Baader harangues Meinhof mercilessly about her foul-up; Meinhof meekly accepts the abuse.

Much of this chapter will also detail the numerous recruits that join up during their first few months back in Germany. Though Mahler and three others are captured within weeks of the gang’s return from the Jordan desert, at least ten other comrades join up to replace them.

In late December several gang members are involved in a shoot-out with police in Nuremburg. No one is hurt, and two gang members are captured. The shoot-out will present the perfect opportunity to detail the growing support of the Baader-Meinhof Gang among young radicals. Because no one had yet been hurt by the gang’s actions (save for the elderly librarian shot during the freeing of Baader), young radicals are able to give vocal support for their efforts without much reservation.

Chapter 7 — The German Response

Winter 1971, 24 pages: This chapter will mostly explore the way that the Baader-Meinhof Gang began to unwittingly increase the power and cohesiveness of the German state. West Germany was originally created by the Allies after World War Two as a loose confederation of states, mostly to prevent the resurgence of a Germany with the power of Hitler’s Deutschland. Each Länd, or state, had its own police force, with no federal force in place like America’s FBI.

But the exploits of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, who are freely moving between the states and taking advantage of the states’ lack of cooperation, persuade the various Länder to join forces and allow for the creation of a special antiterrorist section of the federal border police (the BKA). This proves to be the camel’s nose nudging into the tent—the BKA would soon begin to grow exponentially in size and power. Germany is finally maturing beyond the weakened state envisioned by the Allies.

Chapter 8 — The Red Army Faction

January 1971 - June 1971, 42 pages: This chapter will follow the Baader-Meinhof Gang as they become a phenomenon within Germany. A portion of the chapter will explain how the growing hip notoriety of the Gang helps inadvertently rescue a major automobile-maker from oblivion—the Baader-Meinhof Gang saves BMW.

As an underground band constantly on the move, the Baader-Meinhof Gang is in constant need of automobiles. They quickly find that the easiest car in Germany to hotwire is the compact little BMW 2000. BMW has spent the previous decade under the constant threat of bankruptcy, their plain yet fast little cars failing to excite Germans. When the Baader-Meinhof Gang unofficially adopts the BMW as their car of choice, the old Bavarian car company begins to shed its staid image. Soon young Germans began to joke that BMW was not an acronym for “Bayerische Moteren Werke” but instead stood for Baader-Meinhof Wagen.” Without ever changing the basic design of their cars, BMW will find the sales of its cars taking a quantum leap in sales over the next few years, as their cars become hip, trend-setting status symbols.

This time period also represents the gang’s first effort to take hold of their own image—an image that heretofore had been completely dictated by the press. Meinhof writes up a manifesto and Baader designs a logo; they name themselves “The Red Army Faction.” To their chagrin and frustration the press will continue to refer to them as “The Baader-Meinhof Gang.”

This chapter will also revisit various members of the Kommune I, the people who had first inspired Baader and Ensslin to burn down the Frankfurt department store in 1968. Now many of the members have formed their own terrorist band, the Movement 2 June, and have adopted West Berlin as their turf.

Chapter 9 — The Crazy Brigade

February 1971 - winter 1972, 16 pages: This chapter will step back from the Baader-Meinhof story for a bit and focus on a young psychiatrist named Wolfgang Huber, who is employed at Heidelberg University’s outpatient clinic for students. Fully a man of his times, Huber has developed a unique brand of Marxist psychiatry; for Huber, all of his patients’ mental disorders spring from the horrors of Capitalism. It naturally follows that their only cure is Marxist Revolution. When the weary university administration attempts to remove Huber from his post, his patients band together and occupy the administrator’s office. They call themselves the Socialist Patients Collective (SPK), and win Huber his job back.

Invigorated by their success and aware of the Baader-Meinhof Gang’s revolutionary example, SPK begins to explore the idea of becoming terrorists themselves. They carry out a string of remarkably unsuccessful bombing attacks near Heidelberg, and after a few months begin signing their communiqués “RAF” rather than “SPK.” Soon they will be full-fledged members of the Baader-Meinhof Gang.

Chapter 10 — Petra’s Story

June 1971 - July 1971, 16 pages: This chapter will focus on a young gang member Petra Schelm, who is killed in a shoot-out with police in mid-July. Petra’s life will be explored in some detail because in many ways she is perfectly representative of so many of the young radicals who easily found their way into the Baader-Meinhof Gang during this time when the police were completely confounded in their efforts to track them down.

Schelm is a hairdresser’s assistant and sometime student. In early June 1971, she follows her boyfriend into the gang and initially loves the thrill of code names, secret hideouts and guns. After about a month on the run, however, Petra is tired and wants to quit. She tells herself that she will leave the group at the first opportunity to slip away cleanly. Unfortunately, before any opportunity presents itself, she is cornered with a fellow gang member in a police roadblock. Rather than give herself up, she pulls out her gun and two cops shoot and kill her.

Schelm’s death will allow for a return exploration of the growing support the gang is receiving in German society. At this point there are no police officers dead, and yet one young girl from the gang is dead—it isn’t too hard to figure out who are really the bad guys. A remarkable poll is conducted in Germany about this time. One in four Germans express “a certain sympathy” for the Baader-Meinhof Gang, and fully 20 percent of the population indicate that they might be willing to give some form of illegal support to the gang—a bed for the night, money, food—if one of the gang members showed up at their front stoop.

Chapter 11 — The Most Dangerous Game

July 1971 - January 1972, 19 pages: The relative mass support for the gang will shrink considerably over the next few months. Chapter 11 will show the Baader-Meinhof Gang turning deadly. In Hamburg a cop, Sergeant Norbert Schmid, is killed while attempting to arrest a gang member. In early December a member of Movement 2 June, George Von Rauch, is killed in a shoot-out with Berlin police. By late December a Kaiserlautern police officer, Herbert Schoner, walks in on a Baader-Meinhof Bank robbery and is shot dead.

This tit-for-tat nature of terrorist deaths followed by police deaths serves to harden both the support and the opposition for the gang’s activities. For conservatives, the deaths of cops only increases their belief that massive force needs to be mounted to stop the gang. For leftists, the death of the cops are not very troubling because they weren’t exactly innocent victims; they were part of the fascist state apparatus.

After the bank raid death of the policeman Schoner, Springer Press’ Bild Zeitung newspaper publishes a headline to the effect of “Baader-Meinhof Murders On.” Though the headline would later prove quite correct, at the time there is no evidence that the Baader-Meinhof Gang was involved in the raid. Noted German writer Heinrich Böll is incensed and says that Bild’s coverage “isn’t cryptofascist anymore, not fascistoid, but naked fascism, agitation, lies and dirt.” In an attempt to put their violent campaign into perspective, Böll would call the Baader-Meinhof Gang’s efforts “the war of 60 against 60 million.” Böll’s comments reflect a society at large that is hardening its feelings—pro and con—about the Baader-Meinhof Gang. Böll’s association with the proto-revolutionary Baader-Meinhof Gang proves to be no death knell to his own prestige; he is awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature within 18 months.

Chapter 12 — The Quickening

January 1972 - May 1972, 38 pages: With Böll and other prominent leftists supporting their cause, the Baader-Meinhof Gang now has hold of the national conscience as they have never had before. This chapter will explore how the gang begins to feel the necessity to live up to their role as Germany’s self-appointed revolutionaries, and the horrific violence that results.

As the group’s fame escalates, a backlash develops within the core of German leftists that support them. German radicals begin to grumble that the Baader-Meinhof Gang is only interested in tactical actions, such as bank robberies, document thefts, and issuing communiqués. If they are true revolutionaries, when are they going to begin attacking the state? It doesn’t help much when Germany’s other left-wing terrorists, Movement 2 June, bomb the British Yacht Club in Berlin, killing a man. It seems that the younger gang is quickly outpacing the veteran terrorists in the race for true revolutionary status. More shoot-outs with the police follow in the coming months; one shoot-out leaves a Hamburg policeman dead, another leaves a young gang member, Thomas Weisbecker, dead.

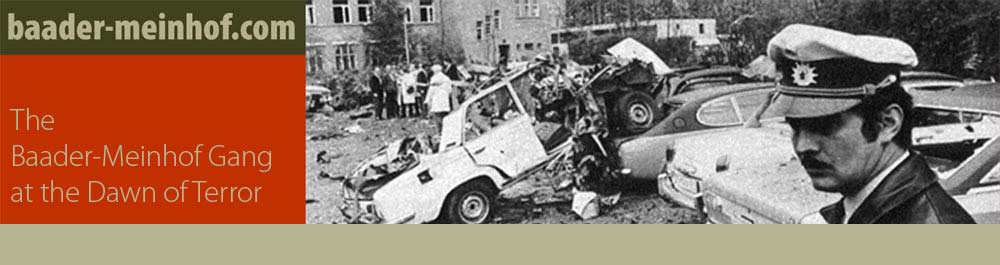

Feeling the pressure of their critics, the Baader-Meinhof Gang provides the definitive, violent answer to their criticism in Mid-May. Ensslin, Holger Meins, and Jan Carl-Raspe leave three pipe bombs in the officer’s mess in the US Army V Corp headquarters in Frankfurt on May 11. Lt. Colonel Paul Bloomquist is killed when a shard of flying glass lodges in his jugular vein. The following day Angela Luther and Irmgard Möller sneak two bombs into the Augsburg police department; the resulting explosion injures five policemen. That afternoon Baader, Meins and Ensslin leave a car bomb in the Munich office of the Bundeskriminalamt. The explosion that follows destroys 60 cars. Two days later Baader, Raspe, and Meins plant a bomb under the car seat of Federal Judge Wolfgang Buddenberg—the man who had signed most of the Baader-Meinhof arrest warrants. Buddenberg’s wife uses the car before her husband and miraculously survives the explosions, albeit with severe injuries. Four days later Baader-Meinhof Gang members place six bombs throughout the Hamburg offices of Springer Press. Three fail the explode, but the other three injure 17 typesetters. Five days later Irmgard Möller and Angela Luther drive two cars onto the Campbell Barracks of the US Army Supreme HQ European Command in Heidelberg. Later three US soldiers are killed. Captain Clyde Bonner is blown into so many small pieces that the police have to collect his body in a pillow case. Specialist 4 Charles Peck is crushed to death when a Coca Cola machine falls on him.

These two weeks in May cause much soul searching among the leftist community in Germany. Before, the actions of the Baader-Meinhof Gang seemed exciting and fun—young radicals could live vicariously through the revolutionary escapades of the gang. But now, with this deadly turn of events, most of the Germans who had voiced tacit support for the group turn their heads in shame. Never again would they give knee-jerk support for left-wing “revolutionaries” without the lingering scent of rotting corpses wafting into their noses. For many Germans an era is over; the golden age when Baader-Meinhof-style terrorism was not perceived to be the work of pathological extremists, but instead represented the legitimate vanguard of the political discourse of the day.

Chapter 13 — Capture

May 1972 - June 1972, 19 pages: This chapter will be mostly straightforward narrative, following the successful effort to capture most of the gang leadership over the next few weeks. The loose confederation of supporters who had provided housing, transportation and money begins to crumble. On June 1, a disillusioned Baader-Meinhof supporter tips off police with the location of a gang hideout. Hundreds of police, with machine guns, rocket launchers, and tanks, converge on a Frankfurt machine shop to ferret out Baader, Raspe, and Meins. German television covers the entire three-hour standoff live as a Raspe and Meins are captured with little struggle, and then Baader, ever the fashion plate, is pulled from the garage with Ray-Bans on his face, and a police bullet in his thigh.

The ensuing week Ensslin is captured in Hamburg when a clothing boutique clerk notices a gun in her purse. The next day several other gang members are captured in Berlin. The following week Meinhof is captured in Hannover along with fellow gang member Gerhard Müller. At first police are not sure that it is indeed Meinhof. One of the police remembers that a recent magazine article had featured a photo of the X-ray taken of the Meinhof’s head after her brain surgery in 1962. Meinhof is taken to a hospital, sedated, and x-rayed again. The telltale metal clip proves Meinhof’s identity. In two short weeks the entire leadership of the Baader-Meinhof Gang has been captured.

One of the more amusing incidents happens a few months after Meinhof’s capture. Police arrange for an identity lineup featuring Meinhof and several actresses. When the police bring in a witness to one of the bank robberies that Meinhof had participated in, she begins screaming, “I am Ulrike Meinhof! Swines! This is all just a show!” The actresses are instructed to follow Meinhof’s lead so the witness is treated to the unforgettable spectacle of a real life version of the “To Tell the Truth” game show--five women, tearing at their dresses and hair, each screaming that they indeed are the true Ulrike Meinhof.

Part Three — A Country Divided Against Itself

Chapter 14 — The Dead Section

June 1972 - February 1974, 16 pages: The various Baader-Meinhof defendants are spread in prisons throughout the German Federal Republic. Meinhof is moved into the “Dead Section” of Cologne’s Ossendorf prison. The entire prison block is empty, save for Meinhof. Everything in her cell is painted white, and her fluorescent light is left on 24 hours a day. Meinhof endures nine months of this psychological torture. Most of the Baader-Meinhof defendants begin hunger strikes to protest their conditions. One of the major defendants, the impassioned former film student Holger Meins, starves to death. Six foot four inches tall, Meins weighed less than 95 pounds at death.

This chapter will revisit the societal attitudes towards the gang. As the seven dead victims fade into memory, many German leftists begin to find themselves outraged by the conditions that the terrorists are being held in. Amnesty International lodges an official complaint with the West German government over the conditions of Ulrike Meinhof’s imprisonment, but the government is unmoved. Early in 1973 they organize a crack antiterrorist commando squad, the GSG-9.

The chapter will end with a visit to Meinhof by her daughters Bettina and Regine. It will be her last contact with her beloved “mice.”

Chapter 15 — The Most Secure Prison Block in the World

December 1973 - December 1974, 14 pages: Throughout 1973 and 1974, the German government prepares for the massive Baader-Meinhof trial. Early on it is decided that the trial should be held in Stuttgart, but the authorities are worried over possible rescue attempts during the course of the lengthy trial if the defendants are transported to a courthouse everyday. The solution is to build a courthouse on the ground of Stuttgart’s imposing Stammheim prison.

No expense is spared in building the courthouse. The roof is covered in spikes to prevent any rescue attempts by way of a helicopter landing, and the walls are made of hardened concrete. All told the cost of building the courthouse tops $5 million. As the courthouse nears completion, the major defendants, Meinhof, Baader, Ensslin and Raspe are moved to a special prison block in Stammheim prison, which is billed as the most secure prison block in the world. Unbeknownst to any of the defendants, the German government secretly, and quite illegally, installs bugs in the cells of the all of the defendants.

The Baader-Meinhof defendants become a cause celebre amongst leftist Europeans. Existentialist Marxist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre visits Baader in Stammheim, lending considerable credence to the notion that the Baader-Meinhof defendants are indeed political prisoners.

Chapter 16 — Lex Baader-Meinhof

December 1974 - January 1975, 8 pages: This chapter will detail the extreme measures that the German government is willing to utilize to stamp out terrorism. The Bundestag rams through a series of amendments to the German Basic Law—their constitution—which are aimed squarely at the Baader-Meinhof Gang. The laws, which become known as Lex Baader-Meinhof, allow a judge to exclude a lawyer from defending a client merely if there is a suspicion that the lawyer has “formed a criminal association with a defendant” (one lawyer finds himself excluded for referring in a letter to his client as “comrade.”) The new laws also allow for trials to continue in the absence of a defendant if the reason for the defendants absence is of the defendants own doing, such as if they are ill from a hunger strike. An international outcry from civil rights activists, especially in the United States, is loudly felt. Four prominent American lawyers, including Chicago Seven defender William Kunstler, and former US Attorney General Ramsey Clark, fly to Germany to officially protest the laws.

These laws will present a good opportunity to discuss the important role of the Baader-Meinhof lawyers. While lawyers are being excluded left and right for perceived philosophical support for their jailed clients, leftist Germans are outraged. The irony is that the German government would later prove to be entirely justified in their concern, because many of these lawyers were in fact fully committed to their client’s causes. Many of the lawyers during this time period are smuggling dozens of items into Stammheim, including, incredibly, two pistols. One of the excluded lawyers, Siegfried Haag, goes underground and regroups the remnants of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, which is now mostly comprised of former Socialist Patients Collective members.

Chapter 17 — Gefangener der Bewegung 2. Juni

February 1975 - March 1975, 14 pages: This chapter will be bookended by two terrorist incidents that captured world attention. Late in February Peter Lorenz, CDU candidate for Berlin mayor in the early march election, is kidnapped by Movement 2 June outside of his house. One of the kidnappers is identified as Angela Luther, former Baader-Meinhof Gang member. A Polaroid photo is released early the next morning showing a disheveled Lorenz with a sign around his neck: “Peter Lorenz, Gefangener der Bewengung 2. Juni” — Peter Lorenz, prisoner of Movement 2 June.

The kidnappers demand the release of six imprisoned terrorists, all members of Movement 2 June save for Baader-Meinhof cofounder Horst Mahler. After much discussion the German government agrees, and arrangements are made to fly the released terrorists to the Middle East. Significantly the terrorists do not ask for the release of any terrorists accused of murder; the six they chose are entirely palatable. Mahler refuses to go, but the other released terrorists board a plane with former Berlin Mayor Heinrich Albertz, who will fly with them to ensure their freedom. Albertz, once a villain of leftists because of his support of the brutal police actions that led to the death of Benno Ohnesorg at a Berlin riot on June 2, 1967, is now a hero to many radicals for his about-face after the terrible riot. Lorenz is released unharmed shortly after the imprisoned terrorists are flown to freedom in the Middle East.

Inspired by the “success” of their comrades in the Movement 2 June, the remnants of the Baader-Meinhof Gang take over the West German Embassy in Stockholm. Ostensibly an effort to gain the release of the Baader-Meinhof defendants, the terrorists don’t seem to realize that their action might be perceived much differently than the Movement 2 June action of two months earlier. They kill two German diplomats and say that they will begin killing a hostage an hour until their comrades are released. Before any more action can be taken, an enormous terrorist bomb with faulty wiring accidentally explodes, setting the embassy on fire. One terrorist is killed immediately, and the others, all badly burned, are quickly caught.

Chapter 18 — The Trial of the Century

May 1975 - May 1976, 27 pages: After three years of maneuvers, construction, and kidnappings, the trial begins. It is a monstrous affair: seven presiding judges, over a dozen prosecutors, an equal number of defense attorneys, and hundreds of witnesses. The defendants make sure that the proceedings are grand theater, with constant interruptions and outbursts. Defense lawyers request the removal of the presiding judge Theodor Prinzing 87 times. Finally, after proving that Prinzing is leaking trial documents to the press and lawyers, the defense attorneys succeed in having Prinzing removed on their 88th try.

Chapter 19 — Mother’s Day

May 1976 - September 1977, 22 pages: This chapter will close the sad saga of Ulrike Meinhof. It will feature a vividly drawn description of Mother’s Day 1976. The other defendants, particularly Baader, have grown increasingly critical of Meinhof. With no one left to turn to, she grows increasingly depressed. She knots together several strands of a torn towel, ties the homemade rope through the grate in her cell door, and hangs herself.

At this point in the chapter the narrative will stop to reflect on Meinhof and her troubled life. Surely her suicide on Mother’s Day was no coincidence. Late that night she probably asked herself the same questions that all of Germany had been asking: how could she give up her two beloved daughters for a life on the run? How could she agree to the plan to let them be taken to Jordan to be raised as terrorists, never to see their parents again? At one time the answer seemed self-evident. To be a committed revolutionary meant to break all ties with your past, including parental ties. Several times in the past she had thrown off supposedly integral elements of her character—first her almost nun-like devotion to her church, then later her apparently unwavering commitment to pacifism. If her “new” character didn’t fit her, she was always able to find a new cause with a new cadre of friends. When she abandoned her kids and threw her lot with Baader, she felt that she had finally found the perfect cause to adopt. Of course she knew that this time there would be no turning back. Unfortunately she was quickly moved to the sidelines within her terrorist faction, and she realized that she was no happier than she had been at any other stage in her life. She was out of options this time, save one: suicide.

Chapter 20 — The German Autumn

September 1977 - November 1977, 60 pages: The final chapter will provide a fitting climax to the story. It will primarily focus on the 44 days in the fall of 1997 that have become known as “The German Autumn.”

In April of 1977 the longest and most expensive trial in German history is over. Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin and Jan-Carl Raspe are found guilty of four murders and 54 counts of attempted murder. The defendants settle into their cells in Stammheim prison and begin serving their life sentences. Outside of the prison, the so-called “second generation” of the Baader-Meinhof Gang plots their release.

An abortive kidnapping attempt of Jurgen Ponto, chairman of the Dresner bank, is made in late July. The Baader-Meinhof commandos accidentally kill Ponto, so they are unable to use him as leverage for the release of Baader and his imprisoned comrades. They have better luck a month later.

On September 5th Hanns-Martin Schleyer, former Nazi SS, current head of the German manufacturers association, and perhaps the most prominent businessman in Germany, is kidnapped in front of his Cologne home. The following day a note is sent to the press demanding the release of ten Baader-Meinhof defendants. In the two years since the kidnapping of Berlin mayoral candidate Peter Lorenz, most German politicians had reconsidered their policy of acceding to terrorist demands. Now they are in no mood to release any prisoners, so the kidnappers and the German government settle into a month-long stalemate.

On October 13, four Palestinians (initially aided by several Baader-Meinhof defendants), hijack a Lufthansa Boeing 737 bound for Frankfurt with 88 passengers on board. The plane is redirected towards the Middle East as the hijackers also demand the release of the Baader-Meinhof terrorists. The German government reluctantly begins planning for the possible release of Baader and his comrades, but they also put their crack antiterrorist unit, the GSG-9, on alert.

On the night of October 17 the Lufthansa plane, now in Mogadishu, is stormed by a commando unit from the GSG-9. The Germans kill three of the four terrorists and rescue all 88 hostages unharmed. In Stammheim prison Baader is listening to coverage of the storming of the plane on a smuggled radio. Knowing that all hopes of him and his comrades leaving are now lost, Baader contacts Raspe, Ensslin and another terrorist, Irmgard Möller. Baader uses an ingenious “telephone” system which uses a power line between all of the cells that is unelectrified 23 hours a day. Together the four terrorists seal a suicide pact.

Baader and Raspe each pull out the smuggled handguns that they had carefully hidden in their cell walls months before. They both shoot themselves in the head. Ensslin takes a long strand of smuggled piano wire and hangs herself on the metal mesh covering her window. Möller takes a sharpened bread knife and stabs herself in the chest repeatedly, narrowly missing her heart sac. Möller is the only one to survive “Death Night.”

Leftist Germans cannot bring themselves to believe that Baader, Ensslin and Raspe have killed themselves. How could they have smuggled guns into “the most secure prison block in the world”? How could they have communicated with each other when prison authorities sealed each of their cells tightly each night? How could they have learned of the Mogadishu raid if they weren’t allowed to possess radios? Clearly, felt many Germans, they must have been murdered by the state.

The final part of this chapter will conclusively prove that the three terrorist did in fact commit suicide.

After millions of dollars in destruction, entire new constitutional laws being written, an exponentially more powerful federal government and over 25 deaths, the Postwar German Decade of Terror is over.